Update 3¶

Overview¶

Our goals remain the same from last quarter. We wish to identify which bee families/genera/species are generalists or specialists. We are also working on submitting an abstract to sign up to attend the annual Ecological Society of America meeting.

ESA Annual Meeting¶

Our research team aim to attend the 2021 annual meeting of the Ecological Society of America. At the meeting, we will be presenting our work with a poster.

![]()

We have worked on an abstract to introduce the methods and goals of this project. The following is our tentative abstract:

With the field of big data influencing a wide range of sectors such as government, healthcare, IoT, and more, big data is rapidly growing, and its capability is vast. Recently, large biological interaction datasets have become increasingly prevalent due to greater data collection and storage. Since pollination is an essential process for ecosystem health and food production, we find value in measuring biodiversity in pollinator bees at the family, genus, and species taxonomic levels. Through our analysis, we can develop an interpretation of the specialist versus the generalist. However, we come to find that there exist several sources of bias within the data. By recognizing that the specialist versus generalist definition is not clearly defined, we can work with programming software (Python & R) to clean, visualize, and statistically test our data in order to cultivate a more complex understanding of our motivation. Ultimately, we will construct a machine learning model to differentiate between a specialist and a generalist. Our work and results underscore the gravity of biodiversity measurement on a global scale and will contribute to downstream research within adjacent areas of study.

Progress¶

Reference Data¶

Last quarter we have attemped to create our own criteria for generalist/specialist identification in GloBI data. Starting this quarter, we have been working on comparing GloBI data with a set of reference data provided by Jarrod Fowler. The reference data consists of three tables, each containing a list of specialist bees in one geological region in America (East, Central, and West). In addition, the Fowler dataset includes information about the rarity of each bee species.

Difficulties¶

Some difficulties working with the Fowler data include the fact that we are not quite sure what were Fowler’s standards for deciding on which bee species were specialists. By comparing his specialist bees with GloBI interaction data, we hope to see some consistency in how specialists were defined. Additionally, since the Fowler data was split between the three regions of the US, some bees were considered as specialists in the East, but not in the West, etc. This complicates the situation since we might need to take into account spatial data during our comparisons, but the GloBI dataset is missing latitude/longitude information for roughly 30% of the bee interactions. Also, we realized that if we do not divide the GloBI data into West, East, and Central like the Fowler data, then there might be inconsistencies and conflicting data since GloBI is global while the Fowler data is just for the US. One more difficulty is that Fowler’s data entry is not consistent. For example, in the column for plant information, not every plant has its family, tribe, or genera all listed. Some pieces may be missing. This makes it difficult to extract plant information from Fowler and compare it to GloBI.

Compare specialists defined by GloBI and Fowler¶

As mentioned in our paper abstract, one of our main goals is to figure out how we can utilize large data sources to make discoveries about bee specialization. In order to do this, we wanted to create some guidelines for what it actually means to be a specialist or a generalist. To do so, we used the Fowler citations on specialist bees, and compared it to the degree of specialization as cited by GLOBI.

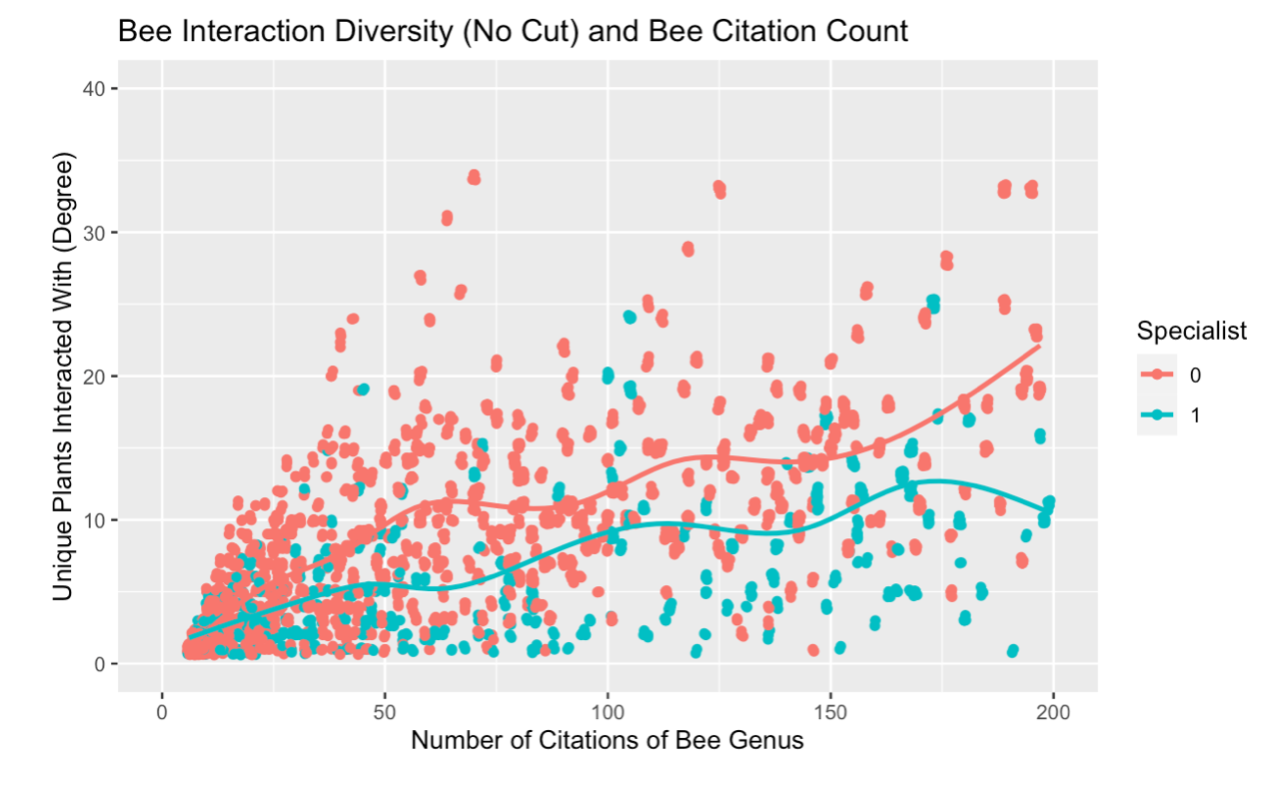

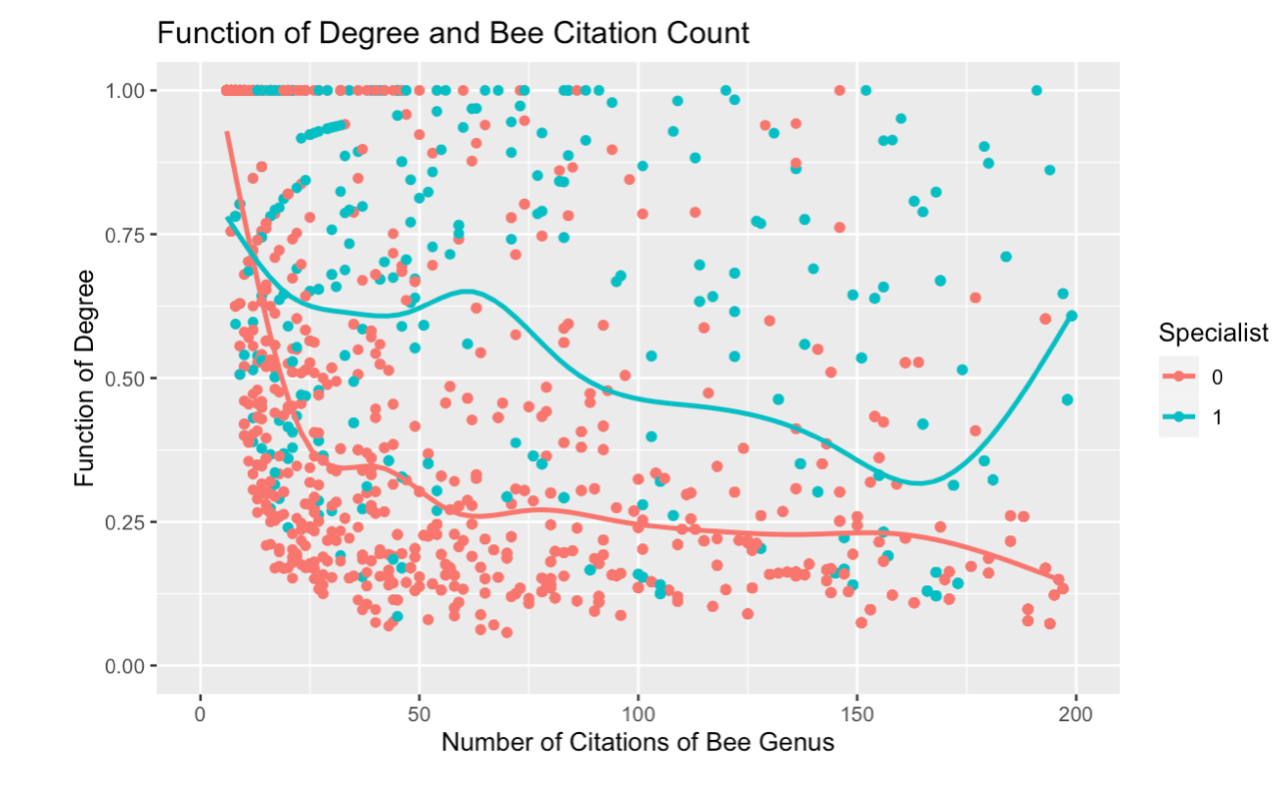

Below is a plot of the GLOBI interaction degree and number of total bee citations. We were able to use color to cluster bee genuses that are qualified as specialists.

Fig. 22 Clusters of bee genus generalists and specialists based on GLOBI degree of specialization and bee genus citation count.¶

Clearly, we can begin to see separation between the two groups as bee citation count increases. Bees with lower degrees of specialization are clearly more likely to be identified in Fowler’s list of specialists. The plot also shows that its clear to determine whether a bee is a specialist or not from the GLOBI data if its citation count is below some threshold (seemingly about 50 citations).

Some major issues still are evident from the plot, though. Clearly, there are generalist bees that have both high citation counts and low specialization degrees! We believe this is a result of a misclassification by Fowler. Since Fowler’s list of specialists is not extensive to all bee genus, it’s very possible that some specialist bees are omitted. Using data from GLOBI in unison with plots like these may be a fantastic way to find these inconsistencies/inaccuracies in Fowler’s list.

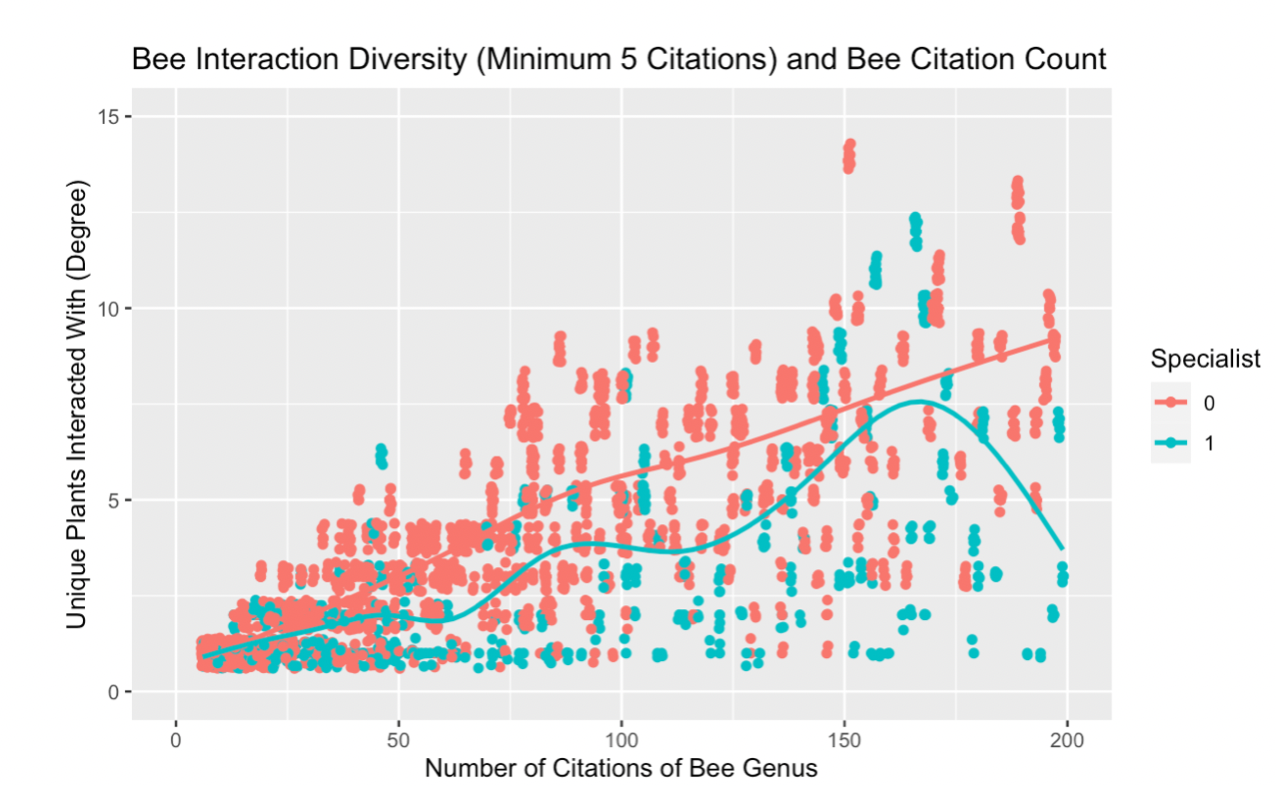

The second major issue that arises is that there remain specialist bees (in blue) that have very high degrees of specialization. We found that this issue likely stems from the GLOBI set. Since GLOBI allows citations from people nationally, there are likely many misclassifications and, as a result, the most valuable citations are those that are repeated multiple times by various sources. Since we consider our degree to include any unique plant family interacted with, bee-plant interactions that have only been cited once or twice majorly increase our degree of specialization. If we only allow plant interactions that are cited more than five times to contribute to our degree, we can eliminate some of these specialist bees with high specialization degrees.

Fig. 23 Clusters of bee genus generalists and specialists based on GLOBI degree of specialization, as we have recalculated using a minimum citation of 5, and bee genus citation count.¶

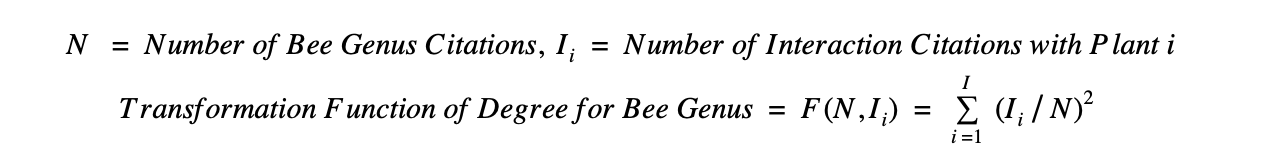

Still, though, there remain many seemingly misclassified specialists and generalists. Since discovering this, we have been trying to find ways to separate the data to minimize these inconsistencies. One such way was to create a function of the degree specialization to transform the data in such a way that would further separate specialist and generalist groups. By summing the square of the percentage of citations an interaction accounts for, we are able to better separate the clusters.

Fig. 24 Clusters of bee genus generalists and specialists based on our transformed function of GLOBI degree of specialization and bee genus citation count.¶

While our data transformation is less practical to understanding how degree of specialization affects specialist labels, it does allow us to further separate the clusters. We hope to make more transformations like these to best understand how labels of generalists or specialists are assigned, and whether it is a consistent qualifier.

Using Fowler specialists as training data for GloBI¶

Our reference data from Jarrod Fowler on pollen specialist bees of the Western, Eastern, and Central United States serves as a validation-like dataset to develop a better understanding of how to define a specialist on our GloBI data. We have been working to assess the relationship between a bee’s status in the Fowler data (Rare, Uncommon-Rare, Uncommon, Common-Uncommon, Common) and its classification as a specialist. In addition, we are exploring the significance of measuring if a bee species is a specialist across all 3 US regions (West, East, Central). We call these bees “true specialists.” More recently, we have been examining the geographic locations of the specialist bees by using GBIF so that we can interpret the geographical constraints of certain specialists that are limited to specific regions. With these considerations of the various attributes of the GloBI data, we aim to create a model or metric that could potentially return results similar to that of the Fowler collection. In order to align the Fowler and GloBI data, we need a count of the number of plant families visited by a bee species and the overall citation count of the bee in the GloBI dataset. We can weigh these variables and translate this into a mathematical formula. Then, we can proceed with training this model on the Fowler data.

Conclusion and Next Steps¶

The introduction of the Fowler specialist dataset has allowed us to more easily pinpoint specialists within the Globi dataset. We aim to create a model or function that measures the degree of specialization that a Fowler specialist shows within the Globi dataset. In order to do this we must take into account the number of citations as well as the number of plant families visited that a specific bee species amounts to. By creating weights for these variables we will be able to come up with accurate degrees of specialization for different bees as the Globi data is continuously updated. Analyzing these changes in degrees of specialization over time will give scientists a bigger picture of what bees may need human interaction in the future.